Cyber Apocalypse 2023 - Reversing - Hunting License

STOP! Adventurer, have you got an up to date relic hunting license? If you don’t, you’ll need to take the exam again before you’ll be allowed passage into the spacelanes!

We’re given a binary that we need to inspect, and a Docker container that we can spawn.

The docker container will ask us questions that we’ll need to answer about the provided binary.

What is the file format of the executable?

>

Running file license on a linux system tells us:

license: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=5be88c3ed329c1570ab807b55c1875d429a581a7, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

So the answer they’re looking for here is ELF.

What is the file format of the executable?

> ELF

[+] Correct!

What is the CPU architecture of the executable?

>

The output from file also tells us this - 64-bit.

What is the CPU architecture of the executable?

> 64-bit

[+] Correct!

What library is used to read lines for user answers? (`ldd` may help)

>

The question helps us here by telling us we can use teh ldd command to find out.

ldd ./license

$ ldd license

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffcd30ae000)

libreadline.so.8 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libreadline.so.8 (0x00007fb1aba90000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fb1ab8bb000)

libtinfo.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libtinfo.so.6 (0x00007fb1ab88c000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fb1abafe000)

Probably they are lokoing for libreadline.so.8.

What library is used to read lines for user answers? (`ldd` may help)

> libreadline.so.8

[+] Correct!

What is the address of the `main` function?

>

Here’s where it started to get tricky. I initially opened up the binary in gdb and ran info functions to get a list of all functions.

gef➤ info functions

All defined functions:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x0000000000401000 _init

0x0000000000401030 free@plt

0x0000000000401040 puts@plt

0x0000000000401050 readline@plt

0x0000000000401060 strcmp@plt

0x0000000000401070 getchar@plt

0x0000000000401080 exit@plt

0x0000000000401090 _start

0x00000000004010c0 _dl_relocate_static_pie

0x00000000004010d0 deregister_tm_clones

0x0000000000401100 register_tm_clones

0x0000000000401140 __do_global_dtors_aux

0x0000000000401170 frame_dummy

0x0000000000401172 main

0x00000000004011e1 reverse

0x0000000000401237 xor

0x000000000040128a exam

0x00000000004013c0 __libc_csu_init

0x0000000000401420 __libc_csu_fini

0x0000000000401424 _fini

gef➤

But, it didn’t like 0x0000000000401172 or 0000000000401172 as an answer.

I opened this in Ghidra and it told me that it was 00401172, which was accepted. I don’t know enough about why gdb pads that many zeros, but hey I still found the answer in the end.

What is the address of the `main` function?

> 00401172

[+] Correct!

How many calls to `puts` are there in `main`? (using a decompiler may help)

>

We’ll need to actually look at the disassembled source code for this. I had it open in Ghidra and could just count, but I wanted to learn more about using gdb. The command to disassemble a function is disassemble functionname, but you can shorten it.

gef➤ disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000401172 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000401173 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000000000401176 <+4>: sub rsp,0x10

0x000000000040117a <+8>: mov edi,0x402008

0x000000000040117f <+13>: call 0x401040 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000401184 <+18>: mov edi,0x402030

0x0000000000401189 <+23>: call 0x401040 <puts@plt>

0x000000000040118e <+28>: mov edi,0x402088

0x0000000000401193 <+33>: call 0x401040 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000401198 <+38>: call 0x401070 <getchar@plt>

0x000000000040119d <+43>: mov BYTE PTR [rbp-0x1],al

0x00000000004011a0 <+46>: cmp BYTE PTR [rbp-0x1],0x79

0x00000000004011a4 <+50>: je 0x4011c6 <main+84>

0x00000000004011a6 <+52>: cmp BYTE PTR [rbp-0x1],0x59

0x00000000004011aa <+56>: je 0x4011c6 <main+84>

0x00000000004011ac <+58>: cmp BYTE PTR [rbp-0x1],0xa

0x00000000004011b0 <+62>: je 0x4011c6 <main+84>

0x00000000004011b2 <+64>: mov edi,0x4020dd

0x00000000004011b7 <+69>: call 0x401040 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004011bc <+74>: mov edi,0xffffffff

0x00000000004011c1 <+79>: call 0x401080 <exit@plt>

0x00000000004011c6 <+84>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004011cb <+89>: call 0x40128a <exam>

0x00000000004011d0 <+94>: mov edi,0x4020f0

0x00000000004011d5 <+99>: call 0x401040 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004011da <+104>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004011df <+109>: leave

0x00000000004011e0 <+110>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gef➤

I count 5.

How many calls to `puts` are there in `main`? (using a decompiler may help)

> 5

[+] Correct!

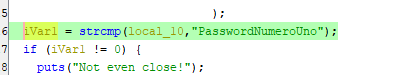

What is the first password?

>

The main function doesn’t ask for a password directly, but it does call exam().

This is where I switched to Ghidra, because it’s a bit more friendly to navigate.

Looks like this one is just in plain text in the source.

What is the first password?

> PasswordNumeroUno

[+] Correct!

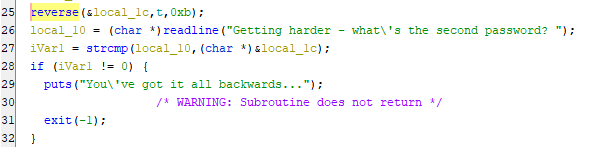

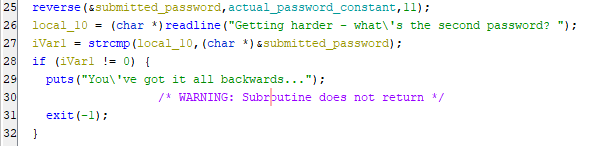

What is the reversed form of the second password?

>

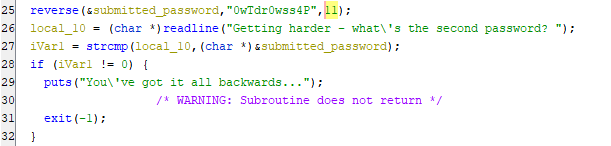

Further down in the exam method we see where it’s asking for a second password, and it looks like it’s been reversed using a function named reverse.

In Ghidra we can rename variables when we figure out what they are to make it easier to understand what’s going on. We can also change the hex values to decimal so they are easier to understand. This function appears to reverse a string, and it indicates that the string is 11 characters long.

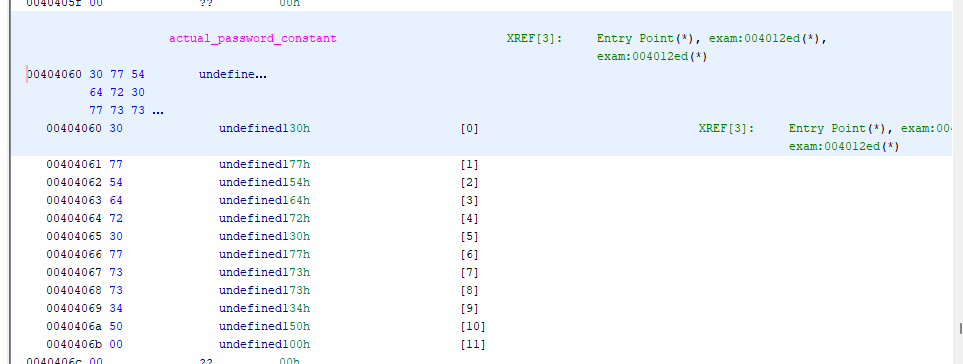

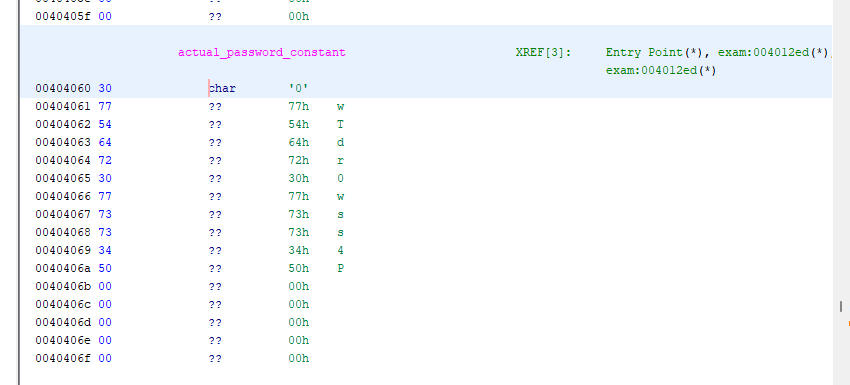

The actual_password_constant is a string constant that we should be able to find in memory. Double clicking it takes us to where it is stored.

I learned some tricks to help understand things stored in memory like this.

First, we can change how Ghidra is displaying the values of stuff here. Right clicking the top/highlighted memory address, we can go data -> char to see characters instead of bytes.

Next, we can specify that this is a constant, so it will just show up in the source code instead of looking like a variable. Right clicking the top memory address again (00404060) and going data -> settings, finding mutabliity, and setting it to constant.

Now it’s right in the source code and we can easily copy and paste it out.

What is the reversed form of the second password?

> 0wTdr0wss4P

[+] Correct!

What is the real second password?

>

Now it wants us to reverse it, as it would expect the user to type in. It looks like in this case, reversing it was an attempt to obfuscate it from the source code or from programs like strings… it didn’t work very well.

I just used VSCode to reverse it to save time.

What is the real second password?

> P4ssw0rdTw0

[+] Correct!

What is the XOR key used to encode the third password?

>

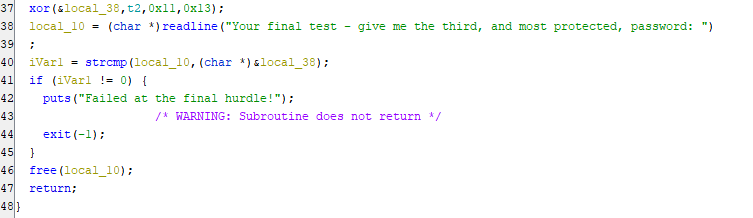

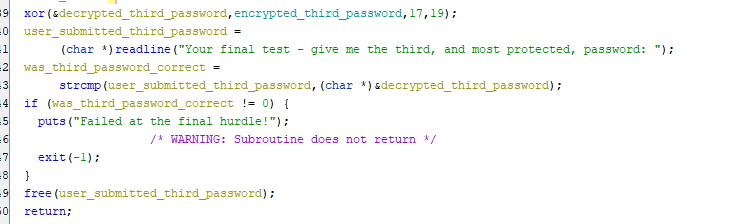

Here is the section for the third password.

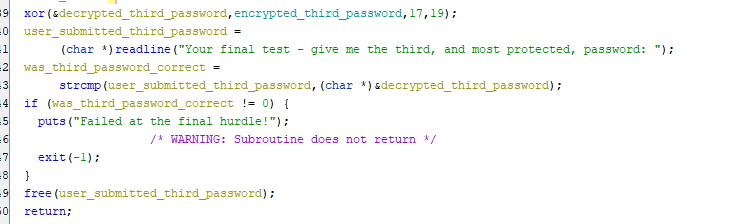

Here it is cleaned up a tiny bit so it’s easier for a human to read.

Looks like there’s an xor function here for the second password, which probably decrypts the password in order to compare it to the plaintext the user would type in. Because I had figured out what the first and second variables were, I knew the key had to be either of the provided numbers, and the other number would likely be the length. I could have spent some time figuring out the xor function, but instead I guessed and got it right on the second try - the answer they wanted was 19.

What is the XOR key used to encode the third password?

> 19

[+] Correct!

What is the third password?

>

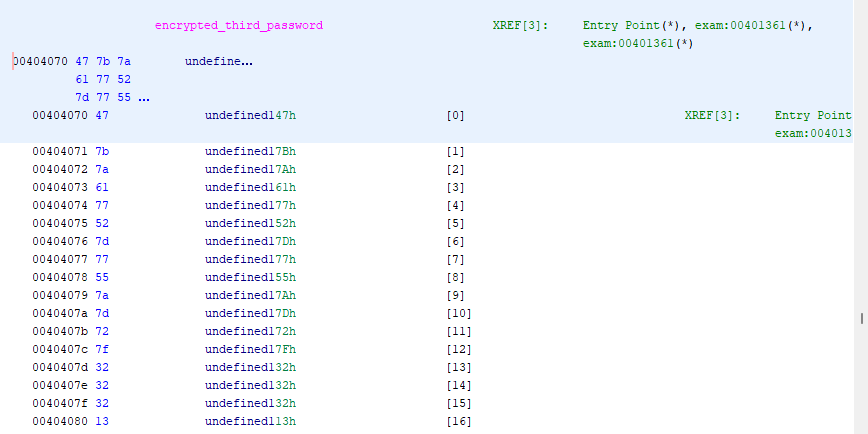

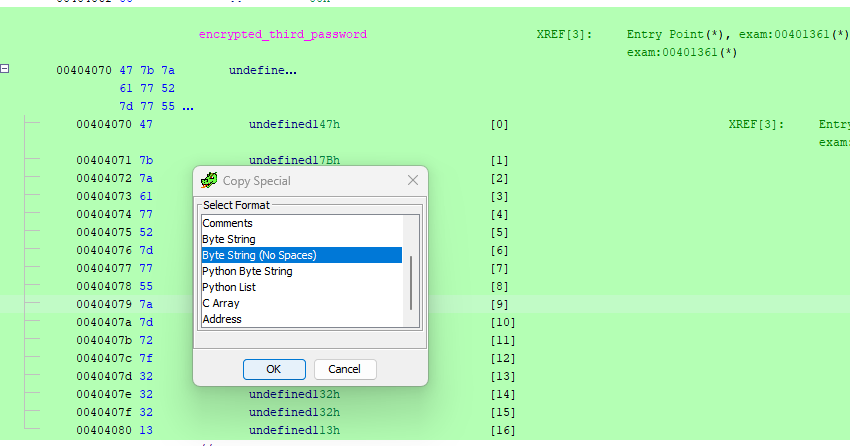

The third password is a constant in memory, like the second, but it’s encrypted and stored as a series of bytes rather than characters - so we can’t display it like we did the previous one. Since XOR’ing works on bytes, not on characters and strings, we’ll need to get the bytes of this constant out in order to work with them. We can select all of the memory addresses in this section by clicking the top on (00404070) and SHIFT+Clicking the bottom one (00404080). Then we can right click the selected area and go Copy Special… -> Byte String or Byte String (No Spaces).

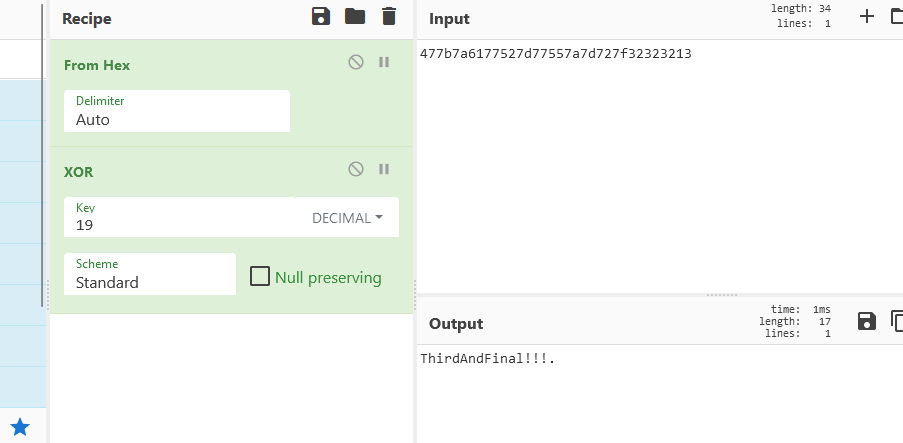

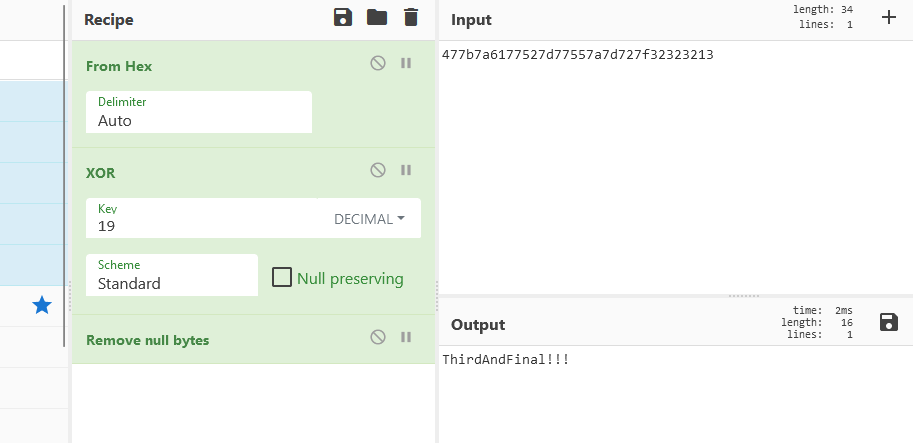

Now we can play with this byte string in CyberChef.

The values we got are in hexadecimal, so our first operation should be to convert them From Hex. Then we can add the XOR operation - or the XOR Brute Force if we’re lazy, though that will only work here because the key is so short - normally it would be much longer. We do know the key, so I’m going to choose just normal XOR. Remembering to set the key to Decimal, to match how I set it to display in Ghidra.

Cyberchef adds . characters when it doesn’t know what a character is, or when it’s null, so I like to add a Remove null bytes at the end of any recipe, to clear these out.

And we have our third password, and the flag.

What is the third password?

> ThirdAndFinal!!!

[+] Correct!

[+] Here is the flag: `HTB{l1c3ns3_4cquir3d-hunt1ng_t1m3!}`